Learning About PFAS

The port provides drinking water for some industrial tenants, marine vessels, irrigation, and fire protection. It also provides water for some port employee office buildings.

The port’s annual Drinking Water Quality Report has consistently confirmed that the port conducts water quality monitoring in compliance with state and federal health standards for drinking water.

Like other drinking water purveyors across the country and in Clark County, the port is addressing an emerging issue with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). The Washington State Department of Health (DOH) has established a deadline to test PFAS levels for Group A Non-Transient/Non-Community potable water systems – which includes the Port of Vancouver USA’s water system — of December 31, 2025. The port has acted in advance of that date to test its water system.

PFAS Overview

PFAS are human-made chemicals commonly used since the 1950’s in making products like food packaging, outdoor clothing, non-stick pans, certain types of firefighting foam and others.

PFAS are a global public health concern, and exposure to levels above recommended limits over time may lead to harmful health effects.

In June 2024, the port’s Drinking Water Quality Report announced the port’s plans to test for PFAS later that summer. To comply with DOH requirements, the port’s annual Drinking Water Quality Report will include information about PFAS detections in 2025. That information is also shared on this website.

PFAS monitoring at the Port of Vancouver

December 2024: Drinking water samples collected from the Port of Vancouver water system

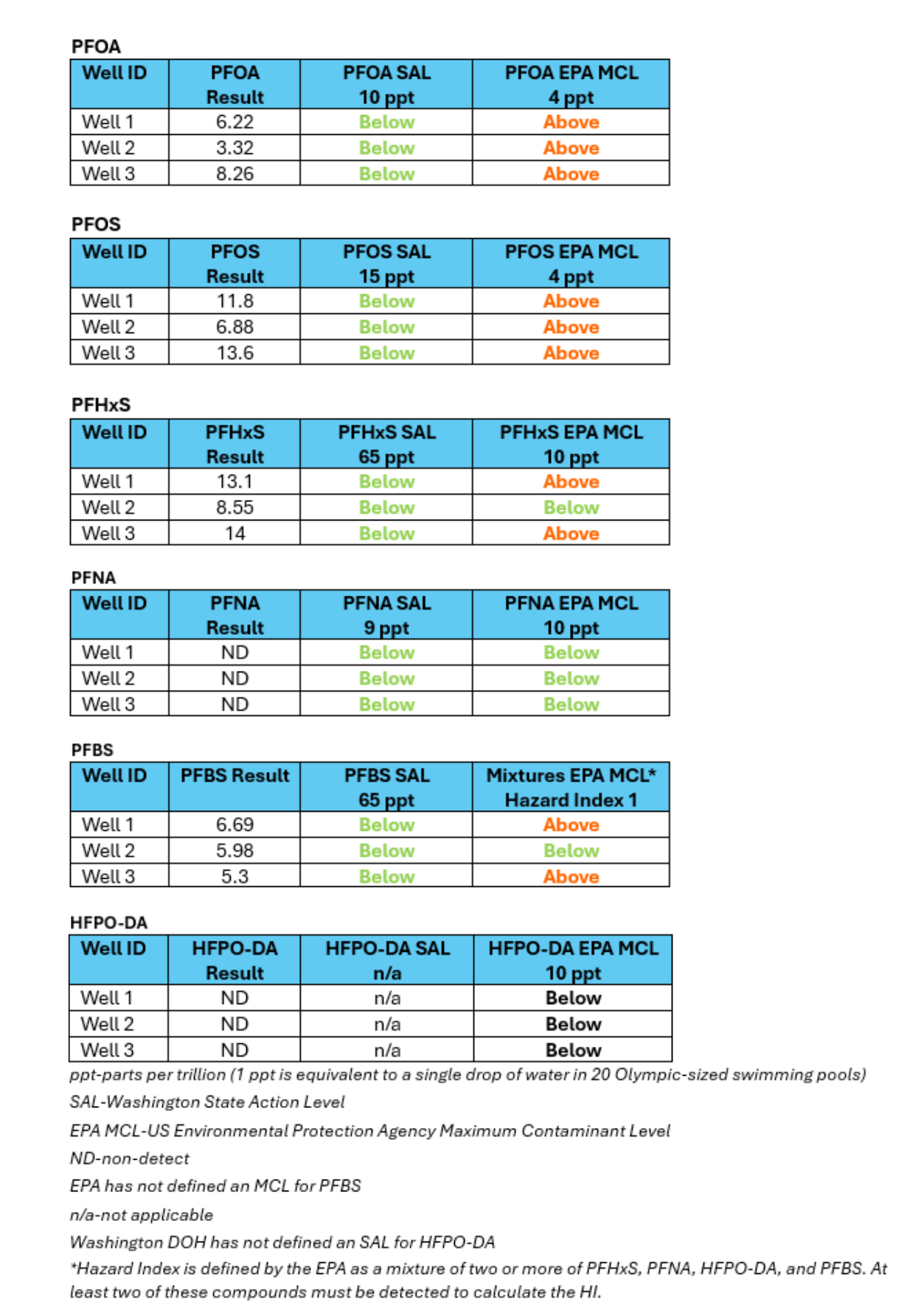

(ID# 688501) included detections of some PFAS. The port initially sampled in August of 2024, in advance of the December 2025 deadline set by the Washington State Department of Health. The levels of PFAS were all below the State Action Levels (SALs) as determined by DOH. However, some forms of PFAS were above the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) new Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs). The port is providing this information so that its water users can make informed decisions.

In April 2024, the EPA set these MCLs for six different types of PFAS. Starting in April 2029, public water systems must take action to reduce levels of PFAS in their drinking water if they are higher than the MCLs. Read more about the EPA’s final rule regarding PFAS here.

PFAS – a regional issue

DOH states that 2,400 Washington water systems have or will test for PFAS. Multiple local municipalities have tested and provided useful information about efforts to address PFAS:

City of Vancouver: Learn about PFAS

City of Camas: Perfluorinated Compounds in Camas, WA Groundwater

City of Washougal: PFAS | Washougal, WA (cityofwashougal.us)

What is being done by the port?

PFAS is an emerging issue for water systems across the country, and has also been detected in public water systems throughout Clark County. The port has taken steps to address PFAS, including:

What do we know about PFAS?

PFAS are a large family of chemicals that are tasteless, colorless, and odorless. They do not occur in nature and are produced to make many products including stain-resistant carpets and fabrics, nonstick pans, fast food wrappers, grease-proof food containers, waterproof clothing, and a special kind of firefighting foam. Over many years of manufacturing and use, these unregulated chemicals have been released into the environment from industrial plants, fire training sites, consumer products and other sources. Once released, PFAS do not break down easily and last for a long time in the environment. Some PFAS have seeped from surface soil into groundwater. Public health officials are concerned about PFAS in drinking water because of new information about their potential human health effects. When ingested, some PFAS can build up in the body and, over time, may increase to a level where health effects could occur. Human health effects of PFAS are still being actively researched and health advice continues to evolve.

Additional information about PFAS is available in the section below.

What are the potential health effects?

There are many different PFAS. We are still learning about their health effects in people.

☐ PFOA. Some people who drink water containing PFOA in excess of the SAL over many years may experience problems with their cholesterol, liver, thyroid, or immune system; have high blood pressure during pregnancy, have babies with lower birthweights; and be at higher risk of getting certain types of cancers.

☐ PFOS. Some people who drink water containing PFOS in excess of the SAL over many years may experience problems with their cholesterol, liver, thyroid, kidney, or immune systems; or have children with lower birthweights.

☐ PFHxS. Some people who drink water containing PFHxS in excess of the SAL over many years may experience liver or immune problems, or thyroid hormone problems during pregnancy and infancy. It is possible that exposed children may have increased risk of abnormal behavior.

☐ PFAS Hazard Index. Low levels of multiple PFAS that individually would not likely result in increased risk of adverse health effects may result in adverse health effects when combined in a mixture. Some people who consume drinking water containing mixtures of PFAS in excess of the Hazard Index (HI) MCL may have increased health risks such as liver, immune, and thyroid effects following exposure over many years and developmental and thyroid effects following repeated exposure during pregnancy and/or childhood.

How can I reduce exposure?

State and federal agencies have prepared resources to address other frequently asked questions:

Washington State Department of Health:

https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2022-02/331-681.pdf

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry:

United States Environmental Protection Agency:

Keeping you informed

By proactively assessing its water, sharing information with water users, and evaluating next steps and potential solutions, the port remains committed to providing safe, clean drinking water for its staff and tenants. Results from ongoing monitoring and steps the port is taking to address this issue will be made available here and shared with water users.

If you have questions regarding drinking water, please call Port of Vancouver USA Environmental Manager Matt Graves at (360) 693-3611. You may also reach us at info@portvanusa.com.

3103 NW Lower River Road, Vancouver, WA 98660

PHONE360-693-3611 FAX360-735-1565 EMAIL info@portvanusa.com

SCROLL